In places like Kenya, the idea of owning a home is still a pipe dream for many. Typically, mortgage lenders would facilitate access to homeownership. But the kind of data lenders rely on — the capacity to pay back the loan, along with available capital, collateral and credit scoring — is still scarce among many Kenyans, particularly in the informal sector. In spite of government intervention and some private sector solutions, the growth of inclusive lending remains slow. Is data access the solution to the housing sector’s woes in a place like Kenya? However, the dynamics aren’t so simple as applying the alternative data formula perfected in other, smaller-ticket digital sectors.

Imagine you’re a Kenyan that wants to build a home. Like most of the other landlords and homeowners in urban areas in Kenya, you’d either have to rely on cash or personal loans. And supposing you don’t use the banks quite often, falling under 56% (or 17.1 million people) of the adult population, then your chances of accessing a large personal loan significantly diminish, as most local banks ask for a bank statement for the past year.

The next option for you lies with informal savings groups or perhaps SACCOs. Through the power of numbers — especially with groups that save with a bank — you can manage to get far larger loans than is otherwise possible. But even then, the potential is limited. In the case of Julius Musau, who is currently building a retirement home just outside of Nairobi, his wife was able to get $3000 USD from her savings group to contribute to construction, which costs a total of about $24,000 USD. Yet with that fraction of the total expenses accounted for, you’d gather your savings, the small loans garnered from the savings groups and your SACCO, and you begin to build. Lay your foundation, perhaps put up some pillars — only to pause once the money dries up, waiting for the next source of funds to manifest.

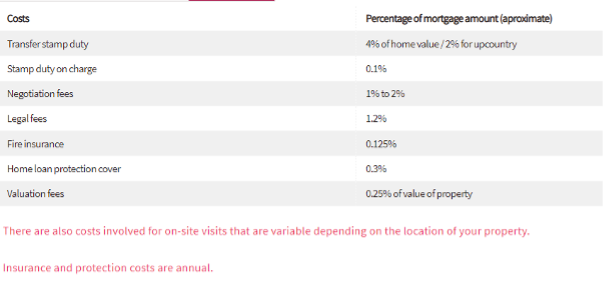

For most Kenyans, it takes years to build a home, and the cause lies squarely in finances. Only 2.5% of bank account holders in Kenya have more than $800 USD in their accounts. Banks offer, on average, loans for 70% of construction costs and often require about a 20% down payment for the loans — excluding the swaths of applicants who fail to even receive such an offer. The financing market saw a deeper crunch after credit extended to private lenders decreased significantlywith the introduction of an interest cap by the government between 2016 and 2019. And while the interest rate cap was scrapped in 2019, interest rates subsequently rose to about 11% to 18%, driven up by multiple additional fees and levies.

Source: Absa Bank, Sample of extra costs on construction loans by a bank in Kenya

The funding gap encourages you, the homebuilder, to save on costs wherever possible. Perhaps your search for the cheapest deals leads you to opt for neighborhood builders without hiring engineers, architects, or developers. Winnie Gitau is the co-founder of KwanguKwako, a construction company that builds affordable alternative housing in Kenya.

“The traditional model of building has a lot of loopholes where people [involved in construction] can steal from the builder. As the homeowner, you would often need to project manage and oversee the materials transportation, delivery, and use, or risk going back into your pockets when some materials go missing.”

Winnie Gitau, Co-Founder, KwanguKwako

Yet building cheap makes maintenance expensive: you would find your house leaking months into moving in, or worse, have the building collapse. And in a country still struggling to offer citizens access to even basic health insurance, housing insurance is quite limited. As the years go by, inflation rates, time spent overseeing the project, and stolen construction material along the way would have you spending almost double the actual price of the building, Gitau adds. All because you couldn’t access finances.

In many markets, mortgages would solve many of these problems, where you could simply move into a pre-built house and make extended payments. But the market is filled with unpredictable interest rates, which could have you paying much higher in the next decade than your starting payment plan. Regardless, the available mortgage products would be too high priced to begin with — and their requirements, often including bank statements and payslips, would leave you out. On top of that, there is a housing deficit of two million homes made even worse by the facts that only 2% of formally constructed houses are targeted for lower income groups. That lowers your chances of accessing an affordable home via the mortgage route and takes you back to the initial option of building your home yourself or staying in a rented house.

It’s convenient to blame the lenders for not having more products out in the market. According to a Kenya Central Bank report, only about 26,723 mortgage loans were granted in 2021 in a country with a working population of over 23 million people. And even then, lenders have focused on providing mortgages to the high-end property market, demonstrated by some banks requiring up to three years’ worth of audited books of account and bank statements, which would be typically unavailable for informal workers. Beyond mortgages, individual loans usually require proof of income sources as well as collateral. When applying for loans to build houses to later rent them out — another popular investment among Kenyans — it’s often expected to provide evidence of previously successful construction projects, which acts as yet another barrier for first-time owners to break into the market.

“Many local banks don’t count the current project [as an income source] for small rental owners. It is considered high-risk and, therefore, zero-rated. They evaluate existing streams of income, locking out people who don’t have extra income streams.”

Winnie Gitau, Co Founder, KwanguKwako

Gitau explains that it’s often necessary to show proof of more than one stream of income to get financed by the banks. It is easier to first get funds elsewhere and build semi-permanent rentals to gain that extra stream of income and history of success in the market before approaching the banks with a request for financing. Considering all the possible variables — including theft, variations of construction material quality and more — banks are unable to accurately oversee the market without utilizing additional resources. A further lack of accessible data on the payment ability of these individuals in the informal sector creates the largest barrier to providing affordable financing to them.

Despite the barriers, financiers are increasingly widening their scope to include low- and middle-income groups in their lending market. This comes especially in the wake of increasing interest rates and stagnating pricing trends for what had been considered income-generating opportunities in the high-end markets.

“The market is in an adjustment phase. You will find today property in the more lucrative areas going for a lower market value than they were just a year ago, and so you’ll see banks and property firms starting to target people lower in the [income bracket] pyramid.”

Joseph Irungu, Contractor in Nairobi, Kenya

As financiers and property firms start to target the lower-income groups, however, the glaring lack of aggregated data can no longer be ignored by the traditional lenders. Financiers have little idea how much it will cost to build a home for an individual or how long it will take. In an ideal market, all these would be set up front and used to determine the risk level and timeframe for loan repayment. But such upfront valuations are not possible, particularly for individual-owned buildings. Approval processes for construction, for instance, take anywhere between six and fourteen months. This leads to a wildly varying total cost of construction.

Compounding such uncertainties is the lack of a centralized construction platform capable of accurately predicting the cost of building. The construction team, materials and process all factor towards differing costs. These significant unknowns subsequently compel high-interest rates and short payment timeframes, if the loans are offered at all. Therein lies the dilemma: the low-income groups are suddenly attractive clients who would benefit from longer loan tenures and lower interest rates — yet their high-risk nature renders such propositions almost impossible for lenders to stomach.

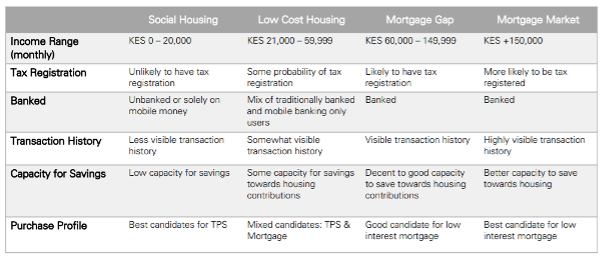

In a bid to make affordable housing a reality, Kenya’s government began an initiative known as the Affordable Housing Program(AHP) in 2017. Its ambitious goals of building 500,000 homes for lower- and middle-income persons in five years were promising at the outset, as they would enable even the lowest income groups earning about $160/month, including those who reside in slums, the ability to live in dignified homes.

Source: Boma Yangu, Allocation criteria for the Affordable Housing Program

The program fell far behind its target at only 2613 units by the end of 2021, but the government’s role in shaping the trajectory of the affordable housing industry cannot be ignored. The program led to the creation of the Kenya Mortgage Refinance Company, a wholesale financial institution providing funds to primary mortgage lenders. With a particular focus on SACCOs and banks, the KMRC is likely to increase mortgage penetration in the market. Its existence and provision of funds have reduced interest rates to single-digit percentages of about 7%.

Despite the lower interest rates, the slow construction of houses under the AHP is insufficient for millions of Kenyans, leaving them with the high-interest financing options provided by banks. These unserved masses represent the market that alternative financing solutions could target.

Even in a fintech-leading country like Kenya, alternative financiers utilizing more innovative credit scoring mechanisms are noticeably missing in action, with very few up-and-coming digitized solutions for the mortgage and home ownership space. Yet there are examples in other emerging markets where tech-based financing options have come into shape. Indonesia’s Gradana, a P2P lending marketplace, started out by connecting borrowers in the property space with lenders. It has since grown to aggregate agents, investors, developers, and financial service providers to provide financing to aspiring homeowners, increasing accessibility. India’s Square Yards, an integrated platform that provides end-to-end real estate services including search and discovery, home loans, property management and transactions. has expanded into nine countries with its powerful marketplace platform.

While these enable data access for interested parties, their contribution to affordable housing remains limited. Granada’s interest rates, about 15-24%, are much higher than the traditional bank loan rates in Indonesia, currently at about 5%.

Such cases abroad shed some light on the lack of alternative financing products in the affordable housing space in Kenya: namely, the difficulty in creating a sustainable solution that lowers the costs for the consumer. A promising solution, RentScore, is a platform that uses rent data to determine creditworthiness for mortgages. Only a few months old, RentScore does offer a glimpse of what’s possible through the use of alternative data sources to increase access to housing while eliminating the need for high-interest rates and the risk-based pricing that banks in Kenya have typically adopted.

Further up the construction supply chain, Jumba, a newly launched B2B tech platform that connects construction suppliers with retailers, has begun the work to demystify the construction process on the demand side. Through solutions like Jumba, the idea is for the widely varying costs of construction materials to level out, trickling down to the clients and resulting in lower-cost homes. Perhaps with more insight into the supply chain, financial service providers and borrowers can access data that accurately prices the cost of construction, leading to better financial products.

For these early solutions to proliferate, however, data aggregation is still sorely needed, a gap that the proptech field has seemed reluctant to take up. The other factors already making such big-ticket lending a more arduous task for fintechs to undertake than other forms of lending — the high variability in cost and time of homebuilding, the lack of history among clients successfully building homes, and of course the sheer costs required among thin-file applicants — renders digitization as both facing more difficulties yet higher need in this sector. In overcoming the considerable cost factors keeping digital solutions at bay, foundations must be built from nothing — and that starts with the right kind of alternative data mining to reach thin-file customers. Any well-constructed house starts with a foundation — and when it comes to an infant digitized real estate industry in emerging markets like Kenya, that work must start somewhere.