The common saying “ask for forgiveness and not permission” has never been more contentious than it is in the current African fintech space. After enjoying regulatory freedom at their inception, fintechs are now grappling with a tightened landscape as regulators finally play catch up with fintech’s innovations and disruptions. Following some of the critical regulatory guidelines manifesting in the past couple years, players looking to innovate may need to readjust their longstanding approach and ask for permission first if they wish to navigate the ever-shifting regulatory environment unscathed.

Where fintech has been synonymous with “moving fast and breaking things,” a do-first approach came naturally amidst regulatory grey areas or a lack of regulation at all several years ago. Digital lenders — headliners of fintech hubs in places like Nigeria and Kenya since the COVID pandemic — especially benefited from the do-first approach operating within gaps in data protection standards. Yet they’ve now been forced to reckon with the fallout from consumers, the media and governments regarding unethical business practices, including harmful debt collection practices and data privacy infringement.

As they now seek forgiveness, it comes at a cost. In Kenya, 40 digital lenders are being audited by the Office of the Data Protection Commissioner (ODPC), accused of violating certain sections of the Data Protection Act of 2019, though the fines faced are still relatively minimal at $38,00 each. Nigeria’s Sokoloan, a digital lender, had already been [fined about 21,000 USD] (https://techcabal.com/2021/08/24/nitda-fines-soko-loan/) for failing to follow data privacy rules.

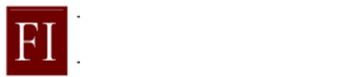

Like Kenya’s data privacy rules, Nigeria’s data protection rules were passed in 2019 as well, but it took some time for their implementation to come into shape. The fintech landscape in 2021 saw increased regulatory attention that’s now disrupting the fintech environment. This comes as more African countries seek to implement their envisioned digital strategies.

Source: APRI

It was in 2021 that Nigeria’s Securities and Exchange Commission issued a notice that technology companies offering investment services without being registered with the commission were operating illegally even where they were in partnership with registered Capital Market Operators. That notice gave rise to the introduction of a sub-broker license that better captured the role of tech companies in the investment services space like Bamboo and Chaka. The crypto space also began to be corralled, as the Central Bank of Nigeria issued a letter to financial institutionsprohibiting their facilitation of payments for cryptocurrency exchanges. This shifted the crypto emphasis in Nigeria towards P2P crypto exchanges, boosting P2P facilitators like Paxful, where Nigeria is now their biggest marketworldwide. Yet perhaps the most disruptive was the [Open Banking Framework], issued by the CBN, whose successful implementation could see innovation and competition increase in the country.

Kenya’s fintech scene also saw some changes that were a particularly large blow to the players who had capitalized on the once permissive regulatory environment. Most notably, the introduction of licensing and supervisionof Digital Credit Providers (DCPs) by the Central Bank of Kenya has had industry-altering effects, leading Google to blacklist hundreds of lending platformsto remain in compliance with the CBK directive. With delays in the CBK’s licensing process, established digital lenders suddenly faced hardships in obtaining funds recently. If the space was once a Wild West, the pioneers of that era are now struggling to prove their compliant credentials.

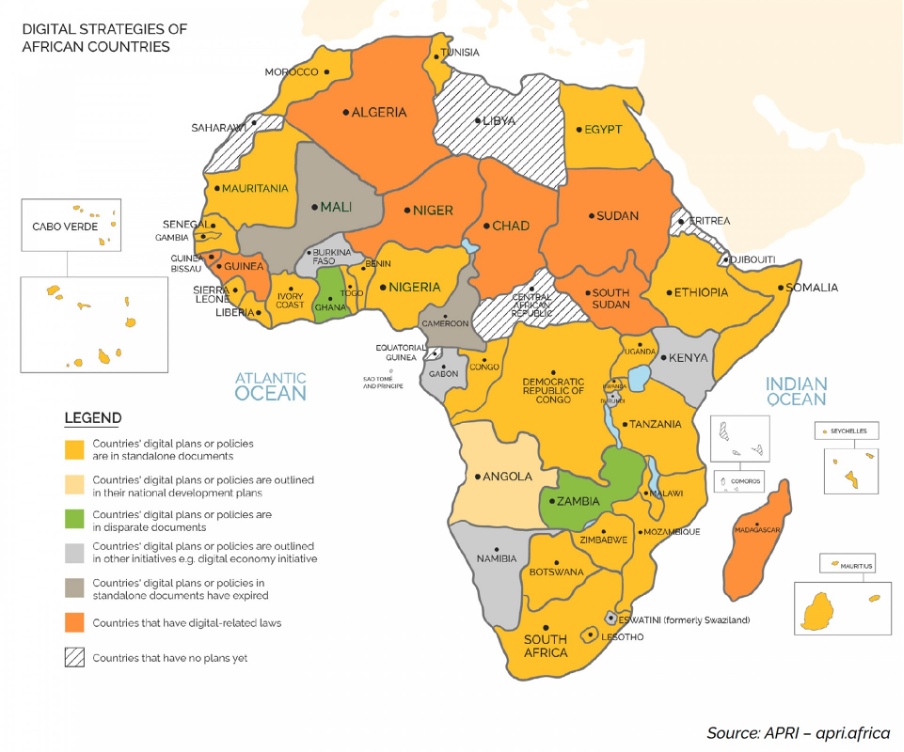

Source: Africa Fintech Radar

The delays involved in acquiring a license have continued for digital lenders, with only a handful of lenders receiving approval months afterward, making a once-saturated market suddenly lacking in fully licensed providers.

With this transforming regulatory landscape, companies that already employed a transparent business model respecting data privacy and security have managed to race ahead. For Karanvir Singh, CEO of Yego Moto, a ride-hailing app in Rwanda, compliance was an essential step from the company’s start in 2016. Yego Moto actively engaged regulators in Rwanda when creating a metering product for their transport services, leading them to receive the first-ever metering as a service license, thereafter launching the product to the Rwandan market.

Yego Moto’s recent entry into Kenya in October was also a testament to its efforts to elicit regulatory permission before operating. Yego Moto hustled to receive a license from the National Transport and Safety Authority (NTSA) before the existing ride-hailing apps had. It introduced a 12% commission, well below the 18% cap on charges to drivers. In a country that has historically taken on quite a permissive approach to regulation, allowing ride-hailing apps, for instance, to determine the commissions, such a permission-centric approach is generally scarce, even among the ride-hailing apps. While the other ride-hailing apps also have their direct charges technically capped at 18%, drivers in the Kenyan market speak of extra booking fees that they get charged, raising the total higher than the stipulated 18%.

“Yes, they reduced the charges, and I am earning slightly more, but they also charge me a 5% booking fee [on top of the 17.24% commission], so we’re still paying them more than 18%.”

Derrick, Bolt Driver, Nairobi, Kenya

Workarounds like those employed ride-hailing apps persist as companies strive to survive in a shifting regulatory space with high competition. Such alleged practices will be a test for how robust enforcement of the new regulatory regime really is.

Whether such regulations winnow the field of competitors is a significant question that will determine the course of such sectors in the near and intermediate term. Yego Moto’s approach worked particularly well, after all, due to limited competition. With few ride-hailing apps in the Rwandan market and a more unfavorable environment for international ride-hailing apps without a presence or substantial investment in the country, the move to work with regulators — and seek to co-create the regulations with them — elevated the company to market dominance, giving Yego Moto a 100% market share of motorbikes and a majority of digital taxis, rivalled only by VW Move. In essence, innovation at this juncture is not the differentiator in Rwanda’s ride-hailing sector — it is compliance.

What had become many fintechs’ go-to solution to emerging regulation — partnering up with more established, already regulated companies to ride on their regulatory compliance status — is quickly turning into a short-term solution. Chaka, a tech provider in the investments space in Nigeria, partnered with regulated brokers Citi Investment Capital Limited and DriveWealth LLC to legally operate in the nation as an investment tech platform, explains Chaka’s former compliance lead, Adedoyin Adesina. But the partnership worked only in the short term, as the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), which provides oversight on the investments space, issued a warning to Chaka to suspend its activities in 2020. The issue? They were purportedly engaging in investment activities without being registered under the SEC, evidenced by their advertisements of sale shares, stock and other securities of companies. As Adesina clarifies, the license in existence at the time did not accurately fit Chaka’s products. Therefore, they couldn’t seek the same license even after getting suspended.

“In hindsight, [Chaka] should have gone to the regulators and said, ‘this is what we want to do.’ When you’ve got a new product, go to regulators [before launching it] and find out what is the best approach, especially when there’s no existing regulation for it.”

Adedoyin Adesina, former Compliance Lead, Chaka

Going to the regulators to ‘figure things out together’ is exactly what Chaka did, finally getting the sub-broker license six months later. But the damage had already been done.

Such cases haven’t stopped the wave of partnerships altogether. In Kenya, Flutterwave, the Nigerian fintech, partnered with Kenya’s financial institutions as a way to expand and operate without regulatory issues. Fingo, a Kenyan neobank, has also partnered with Ecobank, one of the largest banks in Africa, to roll out digital banking services in Ecobank’s 33 markets across the continent. Such partnerships make expansion into new markets possible as the continent awaits cooperation among countries whose focus will be aimed at increasing access and enabling better oversight of the digital agenda.

Source: APRI

But Flutterwave’s partnership with local financial institutions in Kenya has seemingly outlived its importance after the company was accused of operating without approval from the CBK. While Chaka had not sought a license to operate before, Flutterwave allegedly sought a license from CBK three years prior to CBK’s directive for financial institutions to cease working with the company. The directive may have been accelerated by allegations that the company was involved in money laundering, but it does raise the question of how effective partnerships are in jumping regulatory hurdles in the long run.

The emerging consensus is that partnerships without necessary approvals for the new entrants are unlikely to save fintechs from regulatory hot water. Fringo’s partnership announcement, which was coupled with the news of receiving approval from the Central Bank of Kenya — its only country of operation currently — hints at a more stable partnership path focused on synergistic capabilities among partners rather than sheer regulatory avoidance. In this new era to come, partnerships will be morseo a bridge to regulatory engagement for new entrants.

The era of fintechs applying a do-first, ask for forgiveness later approach is quickly abating as regulations catch up with current innovation. It is increasingly essential to seek out regulators to co-create regulations or to get approvals before launching disruptive products and services. By doing so, fintechs have a chance to help shape current and future regulations and position themselves accordingly.

“We’re going to need a change in the current mindset of fintechs. Once you’re regulated, you have to make changes in investments and approach things differently, putting a focus on compliance early on.”

Nicola Muriuki, Director of Legal, Tala

Especially considering the wider economic and funding downturn, this will make for even more difficult times for pioneering fintechs accustomed to the lax ways of yesteryear. But for those that quickly adapt and ask for permission first, the opportunities are there in a still-growing digital economy.